When I was studying for my PhD, I wrote an essay about visiting the grave of my paternal Grandmother in Hay, NSW. I never knew my grandparents on either side; they were all dead before I was born. I was very struck by my mother’s stories of my father’s family, especially his mother. My mother knew her briefly; she died at the age of fifty-six. Far too young. Her heart was weakened, perhaps, by her hard life in the outback, on my grandfather’s small leaseholding on the Lachlan. She had five children (my father was the youngest) and lost her eldest son when he was only 19; he died of pneumonic flu. They were not well off, and it must have been a hard life without much household help. When I looked for her grave, I could not find it at first, until I found an old man limping around the cemetery. He remembered my family, and led me to the non-denominational part of the cemetery. She was born and raised Presbyterian, so although she joined the Anglican church when she married my grandfather, the Anglican minister refused to allow her to be buried in the Anglican section. However, my grandfather had given her a large and impressive tombstone, with the words Love’s Last Token engraved on it. When I was studying for my PhD, I wrote an essay about my search for her and for the origins of my family, and it was published in Antipodes: A North American Journal of Australian Literature.

Here it is: a longish read, but I think you will enjoy it.

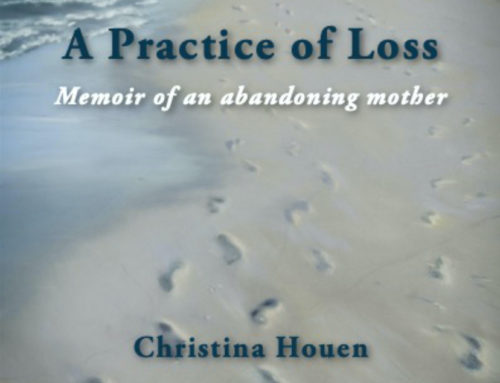

Love’s Last Token: The Desire for Lost Lives and Origins

An unhappy family revisited

MY FAMILY BROKE APART WHEN I WAS EIGHT YEARS old. My father, after twenty-five years of struggling to make a living on a small leasehold on the banks of the Murrumbidgee River, near Hay, New South Wales, had an affair with the cook on a neighboring station, and left his family to pursue his desires. My mother stayed on, and ran the property herself, with help from my brothers, when they were not away at school or university, and from me.

By the time my father left, the property was about eight thousand acres and was sandwiched in between large stations many times its size. Beyond the fertile river paddocks, which were flooded from time to time, the land was red soil, flat and bare, much of it stripped of topsoil during the great dust storms that followed years of drought in the early 1940s. These storms had the unexpected benefit, according to my mother, of bringing with them the seeds of annual saltbush, a silvery-grey creeping ground cover that stores water in its tiny succulent leaves, and not only holds the soil together, but provides the sheep with feed when all other grasses fail. Moreover, it helps the sheep grow sweet meat and fine, strong wool.

When my father left, the property was burdened with a large debt to the Rural Reconstruction Commission, which had come to the rescue after the Great Depression and years of drought had destroyed the flocks he had bred for fine wool. In the last years of the 1940s, the seasons improved, and the wool fetched bumper prices, enabling my mother to pay off the debt. My father kept title of the property, and took the income, providing a legally agreed allowance to my mother for living expenses and running costs.

Six years after he had left, when I was away at boarding school, he returned and evicted my mother, resuming possession of the farm so that he could sell it.

In 1988, I visited my father in the central Queensland town where he lived, forty years after the last time I had seen him. I desired reconciliation and the restoration of the relationship that had been both the source of my greatest happiness and the destroyer of my childhood. I asked him why he hadn’t replied to the letters and gifts I had sent him in the first few months after he left. He was unable to answer me, except to say he hadn’t received my messages. His justification for cutting off contact and repossessing the property was a rehash of the long, rambling complaints he’d written to me in the last few months, since I’d broken the silence by writing to him. His letters were written at first on an old typewriter, in erratic, uneven lines, with gaps where there shouldn’t have been. When his typewriter gave out, he wrote by hand, in spidery ghosts of the strong, distinctive characters I remember from childhood. I listened, but I resisted his words. His recollection of the past had great gaps in it. He’d re-written the story to fit in with his desire for justice and reconciliation, making out he was the only wronged one.

When I was leaving, he gave me a Chinese vase that had belonged to his mother. I wrapped it in clothes, and brought it back to Perth in my suitcase.

Behind the scenes

The vase stood on the polished German piano with walnut inlays, another relic of my father’s family. Both pieces were incongruously beautiful, exotic in our white ant-eaten cottage. As a small child, I studied the pictures painted on the vase’s bulbous belly, and wondered about the richly costumed figures. Two men pose on one side, one on the other. Their costumes, in colors of red, ice-blue, and biscuit, are decorated with gold and black. The styles are flamboyant—gathered culottes with sleek lower legs encasing well-muscled calves, long sleeves generously puffed above the elbow or billowing round the wrist, embossed sashes sculpting the waist. The pictures tell a story of power, conflict and wealth. As a child, I had no key to decode this tale, so I made up my own plots. Now, when I look at it, I notice that the vase is feminine in its shape, with a generous bowl, like a pregnant goddess’s belly, surmounted by a slender torso sloping out, cut off at the shoulders to open into the belly below and accept offerings of flowers. This shape and the color—palest peach—represent, for me, the hidden lives of the women and men who served and supported the powerful figures celebrated by the artist.

To the ordinary man.

To a common hero, an ubiquitous character, walking in countless thousands on the streets. In invoking here at the outset of my narratives the absent figure who provides both their beginning and their necessity, I inquire into the desire whose impossible object he represents. . . .

This anonymous hero is very ancient. He is the murmuring voice of societies. In all ages, he comes before texts. He does not expect representations. He squats now at the center of our scientific stages. The floodlights have moved away from the actors who possess proper names and social blazons, turning first toward the chorus of secondary characters, then settling on the mass of the audience. . . . Slowly the representatives that formerly symbolized families, groups, and orders disappear from the stage they dominated. . . .

—Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life (v)

Michel de Certeau theorises that marginal groups of people in society find ways or tactics of disguising or transforming their desires so that they can have a secret or inner life behind the dominant structures of power imposed by elite groups in society. Thus they can be “other” within the colonization that outwardly assimilates them. I take the “impossible object” of desire represented by de Certeau’s common man to have many faces, according to the gender, culture and time of the “absent figure.” But all the faces have in common the desire for representation and recognition. The Cantonese vase is a coded representation of the desires of a dominant class. For my grandparents, whose ancestors were from the European middle classes, it may have been an exotic representation of their desires for the elegance, wealth and power of the ruling classes. Behind the scenes, and suggested in the vase’s shape and color, I imagine the hidden desires of the marginalised groups supporting the upper classes and dominant gender.

In this essay I identify, not with the primary characters, but with the ordinary women and men who are invisible in this scene. The vase is my talisman, the magic carpet that empowers me to revisit my mother’s stories, told to me as a child and recorded in her memoirs, my father’s fragmented narrative, and other representations I have uncovered. My desire is to re-connect my life, which was abruptly exiled from happiness and the context that had given it meaning, with the story of my family’s pastoral life and inglorious endings in the Hay district.

The missing figures

So the books for the Englishman, as he listened intently or not, had gaps of plot like sections of a road washed out by storms, missing incidents as if locusts had consumed a section of tapestry, as if plaster loosened by the bombing had fallen away from a mural at night.

—Michael Ondaatje, The English Patient (7)

None of my grandparents were alive when I was a child. It was as if they were only characters in one of my storybooks. My parents occupied the centre of my universe and the space behind them was empty. I missed out on a whole dimension of family life, knowing only those two adults thrown into painful relief against the empty outback horizon, driven apart into greater loneliness by their inability to share each other’s disappointments, accept each other’s limitations. And then, one day, there were no longer two, only one, and the aching gap where the other had been.

When my mother Anne was in her eighties I gave her a thick exercise book and asked her to write down her memories of our life, of our grandparents’ lives. She had such a rich store of stories; I couldn’t bear the thought of them being forgotten when she died. A day would come when she could no longer tell them. We’d all try and remember what she’d told us, and all we’d have would be fragments, broken pieces of a rich and intricate mosaic she’d been part of, and we’d only glimpsed.

Now, writing this, I find it hard to separate what Anne wrote in old age from what she told me when I was a child. Most of the stories she later wrote down for us were ones she told us when we were young. Many of these stories had been gathered from my Great-Aunt Mary (my paternal grandmother’s sister) and other members of the family, as well as other folk she knew. Anne had a wonderful memory for facts about people, details of their daily lives, and could make it all come to life as she talked or wrote. In her memoirs, she often diverges into lengthy accounts of local people and events that mean little to me, but through it all, there is an Ariadne’s thread, a precious golden filament of words that tell something of the story of our family in that district. I pick my way through the labyrinth of the narrative of forgotten lives and the deeds of men to find a sense of origins that has meaning to the person I am becoming. What Anne felt was meaningful and important to record is not necessarily so to me, and I must search for fragments hidden by another’s preoccupations.

Anne was brought up in an Edwardian family, translated into an Australian metropolis (Wollongong), with a father who was editor of the local newspaper (The South Coast Times), and a mother who was a housewife. In her family, there was a tradition of social commentary and lively discussion of current affairs. This was reinforced by her university education (Bachelor of Arts from Sydney University, majoring in Latin and English Literature). She wanted to be a journalist, but her father felt this was an unsuitable profession for a woman, so she trained as a high school teacher, and taught for a few years before she met and married my father Eric in Hay, where she was teaching at Hay War Memorial High School. She returned to teach there during the Depression years, when the farm could not support the family, hiring a maid to look after her two young children (my eldest brother and sister). During this time, Eric worked as a jackeroo on the neighbouring merino stud station, and visited Anne and the children in town at the weekends.

Anne was a highly literate and well-informed person, who, in her isolated life in the outback, kept her intellect alive in whatever way she could. Eric was an intelligent man who had left school after completing intermediate level at the age of nineteen. His frail health in childhood and the circumstances of his early schooling had affected his academic progress. Anne listened avidly to the ABC, read the newspapers delivered by train twice weekly and books from the circulating library, and discussed current events and politics with any intelligent adult who came her way. Her daily life was a constant round of housework and caring for her family of husband and five children. Yet, within the “proper” place of patriarchal pastoral life, in which labor was segregated and hard, in a harsh climate, and without the conveniences we now take for granted, she seized opportunities for nourishing her inner life and for educating her children. She supervised our Correspondence School lessons, discussed world events, past and present, with us, read stories to us at bedtime, and made sure we listened to the ABC rather than to commercial stations. These were the tactics by which she sustained her intellect and spirit and nurtured her children’s developing minds.

The place of a tactic belongs to the other. A tactic insinuates itself into the other’s place, fragmentarily, without taking it over in its entirety, without being able to keep it at a distance. It has at its disposal no base where it can capitalize on its advantages, prepare its expansions, and secure independence with respect to circumstances. The “proper” is a victory of space over time. On the contrary, because it does not have a place, a tactic depends on time—it is always on the watch for opportunities that must be seized “on the wing.” Whatever it wins, it does not keep. It must constantly manipulate events in order to turn them into “opportunities.” The weak must continually turn to their own ends forces alien to them.

—Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life (xix)

In her passion for telling stories of family members and local people, she stands between the folk role of hereditary storyteller and the more formalized one of local historian/biographer. Her knowledge of history and current affairs was overlaid on her interest in the minutiae of people’s daily lives and relationships. Her retentive memory made her an ideal storyteller, not unlike the old nurse who was able to tell John Aubrey, the seventeenth-century biographer, “the History [of England] from the Conquest down to Carl I. in Ballad” (Aubrey 22). Anne’s literary skills enabled her to turn these tales into the more sophisticated and durable format of memoirs. Unfortunately, they are unfinished. A series of strokes rendered her right hand progressively more use- less, so the writing deteriorates from a delicate upright script to a large, childish one, and the story tails off in mid-sentence. The later years on the farm after my father left, and most of the circumstances of his leaving, are left out of the narrative.

What is right and fair for me to write about someone else? What is right and fair for someone else to write about me?

Children may be “episodes in someone else’s narrative,” as Carolyn Steedman proposes, whether they like it or not; when children turned adults become the authors of such a narrative, however, it is a different story, and the tables are turned.

—Paul John Eakin, How Our Lives Become Stories: Making Selves (160)

I often get frustrated when I read her memoirs, because she says so little about her personal feelings and the everyday life we led in that isolated place. It’s as if she only respected people who had a name, who’d achieved something, and our life was too ordinary and sometimes too painful to record. In seeking to fill in the gaps, to go behind the scenes, I am telling a different story, making her and other family members episodes in my narrative. I am going against her own wish to keep within the family any criticism (whether explicit or implicit) of the actions of my elders. People’s failures and mistakes were recorded if they were not intimately involved with our lives. But as for our own struggles and losses, little is said in her memoirs. The record of our life has many gaps, like those in my father’s story of his leaving, like the missing characters in his type-written letters, like the empty space behind the masculine figures on the Chinese vase. So I have to use my imagination to fill in the spaces.

Anne was the storyteller in our family, the one who wove the weft of the present into the warp of the past, who gave us a sense of continuity in our mundane lives. When we thought our life was a struggle, she’d tell us of our grandparents, and of the order and symmetry they’d created from nothing. The fragments of the story of my family that are woven into this essay are a compilation of my memory of her oral stories, passages adapted from her memoirs, and my imaginative reconstruction of some of the scenes in which her stories were gathered or told. I stand inside the place created in her memoirs to stake a claim within the territory of my family story. My family story is a palimpsest, on which I write over the partly legible records of my parents and others.

Where possible, I have verified times and events from other written records.

The leaseholder and his wife

Who knows whether the best of men be known? Or whether there be not more remarkable persons forgot, then any that stand remembered in the known account of time?

—Sir Thomas Browne, “Hydriotaphia or Urne Buriall” (282)

Full many a flower is born to blush unseen And waste its sweetness on the desert air.

—Sir Thomas Gray, “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard” 533.

I revisit Hay, seventy-two years after my grandmother’s death, a year after my father’s. I search for her grave in the cemetery without success. At last, I find an old man limping around the graves. He is the first person I speak to who remembers my family. He leads me to the section where her grave is. It is marked by a stepped arrangement of marble slabs, with the epitaph:

In memory of Lillie Houen. Beloved wife of George Houen. Died Aug. 27 1924.

“Love’s Last Token”

Wordsworth’s poem from which the epitaph is taken is an apology for the poet’s inability to sing of flowers sketched by a lady who is an English emigrant living (and dying) in Majorca. He gracefully turns this into an imaginative comparison of the flowers with English ones. He imagines her choosing the sweetest flower and asking for it to be sent to her native land as “true love’s last token.” (130).

My grandfather, I believe, knew this poem, and chose the closing phrase as Lillie’s epitaph because of its resonances with her name, with his image of her as an elegant cultivated flower that had bloomed and died in an environment unlike that of her British parents, and with his desire to create for her a memorial to their love. Sadly, they were separated, not only by her death, but by his later death and burial far from her.

I gaze at my grandmother’s tombstone, wondering what sort of woman she was, so loved by her husband, separate from him in death. My grandfather’s grave is not here. He died in Adelaide at the age of seventy-two, in 1933; he had gone there to live with his eldest son some time after his wife’s death. The cause of his death was an attack of pneumonia, brought on by working all day on the roof of his son’s house, installing an off-peak hot water system in a bitter wind.

The interior of New South Wales had been appropriated by squatters, who had no formal right to the land; but in 1840 a license fee of 10 pounds sterling was introduced.

The Land Act of 1861, with various amendments, . . . saw the democratic division of the massive early pastoral holdings to provide land for the increasing number of aspiring land owners, many of whom had profited from the Gold rush in the 1850s, but who were unable to buy land.

—Pat Harvey, “The Sons of Anton Christian Houen” 3, 6.

Antonio George Houen migrated to Australia when he was sixteen and worked as a jackeroo for a while on a large landholding named Illillawa, extending over 150 square miles, in the Hay district of New South Wales. He arrived there in November 1877, on a day when it was 100°F (38°C) in the shade. The town site of Hay, at Lang’s Crossing on the Murrumbidgee, had been surveyed in 1859 (Hay Historical Society 6). Illillawa’s manager had sent a band of station hands in an attempt to chase away the surveyors who came to mark out the site of the proposed town, which fell within the landholding of Illillawa. The resistance failed, and subsequently, Illillawa was cut up into many smaller leases.

The road from Hay to Booligal, fifty-five miles away, was surveyed in 1869. In its heyday, Booligal, separated from Hay by black-soil plains, was a staging-post on the regular mail route taken by Cobb and Co coaches through Deniliquin, Hay, Booligal, Ivanhoe, and Wilcannia from 1886 to 1901 (13). This was before the great droughts of the early 1900s, the beginning of the motor age, and the building of the railways brought an end to the commercial traffic through Booligal.

In 1886, George took a lease on land in the Booligal district and named it The Cubas (after the only trees, a type of acacia, that grow there). In 1892, George married Lillie Nicholson, daughter of a pastoralist in the same district. Lillie’s Scottish father was a renowned stud breeder, married to a spirited, lively Irish woman. My Great-Aunt Mary, Lillie’s sister, told my mother and me many stories of the lifestyle their family had led, depicting it as farm life at its best. Their mother, Mary said, knew all the housewifely arts of preserving fruit and vegetables, curing meat, rendering fat to make soap and candles, sewing and needlework. In the afternoons, when all the housework was done, the girls and their mother would change and put on embroidered black satin aprons, intended to save their frocks from the threads of their sewing, in which they all excelled. I remember many beautiful embroideries Aunt Mary was working on when we called to see her on visits to town. Even in her eighties, she created exquisitely shaded roses and other garden flowers.

As her needle flew in and out of the linen, Aunt Mary described their kitchen.

It was hung with bags of onions, bunches of herbs, flitches of bacon and hams. It was lined with bins. We kept flour and sugar in some of them. We’d fill the others with cakes and pastries we made on baking days. We had a dairy, a cream-house, fowl runs, kitchen gardens, an orchard. We had to produce nearly all our food on the place. We’d get stores of groceries out from Hay two or three times a year by bullock-wagon, but we produced all our own meat and dairy products, fruit and vegetables. We couldn’t rely on the general store in Booligal. It was too far away, and transport was too slow. Besides, it wasn’t refrigerated, and was poorly ventilated. It smelt like a dunny!” She wrinkled her nose in disgust, and laughed, her eyes creasing into dark slits behind her glasses.

Mother and Father ordered household equipment in bulk from Anthony Hordern’s catalogue three or four times a year. It was so exciting when the bullock tray arrived. It would be laden with supplies. Imagine it— there were baskets and barrels of goods, perhaps a clothes basket full of crockery, barrels full of sheets and other household linen. When I was small like you, Christina, the catalogue was my favorite picture book. It was big, thick, and every page was covered with small pictures of the goods in stock. Even farm implements, harness, tools, barrows, sulkies . . .

In her stories of my father’s colonial ancestors, my mother expressed admiration for their energy and enterprise; how they strove to reproduce the bountiful comforts of the life they’d known in their home country here, in this alien, harsh, intractable country.

“They developed a style of house that suited the climate. The typical country home in the Booligal district wasn’t like ours. It had high ceilings, wide verandahs and an arcade running through the centre.”

“What’s an ah-cade, Mum?” I said, only half-listening to her story, weaving pictures of her unfamiliar words into the drawing I was doing. She was a learned woman, who had no-one to talk to outside her family most of the time, and she talked to us as if we were grown up. Many of the words she used became part of my vocabulary long before I learned their proper meanings.

It’s a hall running through the centre of the house. It’s wide enough to live in. Cross draughts flow through it in the hot weather. There are wide doorways at each end, and the other rooms open onto it, so that cooler air from the shady verandahs comes through. There’s gauze on all the doors and windows, to keep out insects, except for those tiny midges that cluster round the lamps at night.

She paused to pour herself another cup of tea from the china pot. She made tea several times a day, and always drank two cups. “I longed to have a cellar underneath our house, like the big station homesteads did. When we first came here, I dreamed of us setting to work to dig one. I wanted a pisé house, too, like some of the ones I’d seen in the Booligal district.”

“What’s pee-zay?” I interrupted.

“It’s like cement, only it’s made from mud that’s been dried in the sun. It makes a house that’s lovely and cool in summer, and warm in winter, and the walls are a soft earth color.” She stared into her cup, then put it down with a clatter on the saucer and picked up the sock she was darning.

“Just think,” she said, her needle moving in and out of the warp she’d woven: “the landscape round here, it must have looked eerie to a visitor from the coast. Imagine how the first settlers must have felt, whether they first saw it in drought-time or when it was thickly covered with flowers and grass. They were used to green hills, woods, villages nestling in valleys, streams and rivers. Instead, they saw flat plain as far as the eye can reach, bare, except for the belt of trees following the river, spreading out to show how far the waters reach in flood-time. But they set to work to fence and build, dig and plant.”

“Think of the summers,” she said, shaking her head. “They weren’t used to the heat and the dryness. The clothes they wore didn’t help. When I first came to Arendal in 1927, there were still old hands—fencers, shearers, and the like—who wore flannel undershirts to sop up the perspiration. If they’d let the perspiration do its work, their bodies would have cooled down naturally, but they thought that would harm them. Think of the women. Your great-grandmother and her sisters wore full cotton dresses, long and starched, covering the body up to the chin and down to the wrists and ankles. That’s how they dressed every day, while they did their work, cooking on hot wood-burning stoves, sweeping, scrubbing uncovered floors, washing in heavy galvanized iron tubs. The tubs had to be filled and emptied without running water. They boiled the white clothes in steaming coppers.”

“Tell me more about grandmother,” I said, as I did pre- tend writing on the brown newspaper wrappers my mother had saved and cut open for me. I wanted to be literate, like her, to decode the mysteries of the written word, to have access to the world of books and writing. In this world where life was hard work, a daily struggle with the climate and the environment, reading and writing was the key to another world, a world of the imagination and the intellect and other more interesting ways of life. I was reared on a diet of fairy stories and tales of the imagination, and spun my own stories of magical worlds in my solitary play. I also observed how my mother was nourished by her reading, which connected her with the world beyond our empty horizon. Yet when I was quite small, I stood in front of her with hands on hips, and said: “I’m not going to University when I’m big!” I resisted the hard work of education yet I longed for the fruits it would bring. Meantime, I filled endless scraps of paper with a spidery scrawl not unlike the one my father’s baroque hand turned into when he was old.

“Well, Lillie’s parents were very sociable. They were hosts to many parties. People would come from all over the district, for picnics and tennis in the daytime. At night, they’d dance on the wide verandahs and in the arcade. One of the daughters would play the piano; per- haps one of the men would play a mouth organ. Your grandfather used to exclaim over the burden of work for the women of the house, but I never heard Aunt Mary complain about that. She just spoke of the fun and romance of those times.” She paused to break off a new piece of blue-grey darning wool, to finish the darn in my father’s sock.

“I don’t know much about your grandparents’ life at The Cubas. Lillie died not long after I met her, so I didn’t have time to hear much from her, or get to know her very well. I know she and George didn’t keep open house like Lillie’s parents did, because George was reserved and aloof.” She sighed, lay down her darning, and stared out the window at the cool umbrella of the cape lilac tree. Its new green leaves were mixed with fragrant clusters of lilac and white flowers.

“Poor Lillie!”

“Why, Mum?” I paused in my scribbles. “What happened to her?”

“Well, she bore four sons in four years, all in September or October. There was one more child after that, a girl— your Aunt Flora. Imagine so many young children to look after, in those conditions. I don’t think they had a servant. They had a succession of governesses, with gaps in between. The boys’ education got very behind, so Lillie persuaded George to buy a house in Hay so the boys could go to the local school. George kept The Cubas on for a few years. He used to ride a motor bike into town at the weekends, until his health got too bad.” She put her darning down, stretched, took off her glasses and rubbed her eyes.

“What about Grandmother?”

“Lillie died in her fifty-sixth year. I think her heart was affected when her eldest son died of pneumonic influenza during the epidemic in 1919. He was an officer in the bank at Newcastle. He died alone at the weekend, and they found his body in his room, after he failed to turn up for work on Monday. Such a sad way to die! He was an extraordinarily handsome young man.”

My father. a young man of twenty-five, had come at dawn to the window of Anne’s lodgings to tell her the sad news of his mother’s death. The family’s grief was intensified by the refusal of the Anglican rector to allow her to be buried in the Anglican cemetery, although she was a regular churchgoer and active helper. She had been baptized a Presbyterian, but after her marriage she’d supported, but not joined, her husband’s church. So that’s why I couldn’t find her grave. I’d been looking in the Anglican section. Even in death, her place was ambiguous. Within the “proper” place of the cemetery, marked out in denominations, she occupies an unofficial space, consigned to the Presbyterian section, though this was anomalous to the way her life had been lived. The institution of the Anglican church declared her an outsider.

Who was Lillie? A woman with the name of a flower, a mother of five children, wife of a pastoralist, an unofficial Anglican, who died at the same age that I was as I stood looking at her gravestone. She died, I think, worn out by her hard-working life in the outback, bearing and raising children without domestic help or modern conveniences. Almost forgotten, now, when all her children are dead. I can only know her as she is reflected through the lives of her husband and children, glimpsed fleetingly in the mir- ror of Anne’s words, remembered in impersonal stone in an obscure corner of an outback churchyard.

The gifts

Though many of Anne’s words didn’t mean much to me as a child, I loved the sound of her voice, weaving a story of past times, people and places. That’s why I wanted her to write them down, before they were lost forever. Her stories are a gift to me, as the Chinese vase is a gift from my father. His gift portrays an exotic scenario of male dominance and power, inscribed on a vase that, in function and shape, suggests the feminine body. His own life was the opposite, in most ways, of this representation; he died crippled and poor after a life of hard work and struggle and an unhappy second marriage, always regretting, as he told me when I visited him for the second and last time, that his love for Anne and his children had gone wrong. “It all went bung,” he said. When I look at the vase, I see, behind its seductive exotic beauty, the hidden story of my father’s abandonment of his own heart’s desires, and all the grief and regret that were the fruit of his and my mother’s broken desires. I treasure the gift because, like the exercise book in which Anne wrote her memoirs, it connects me with my family history (herstory). Passing from Lillie’s hands through his to mine, it carries me back in time to Lillie and her obscure life. It brings me back to Anne’s delicate handwriting, which inscribes the daily lives and acts of Lillie and her husband, their children, the social world they inhabited. Though Anne’s narrative emphasizes the achievements of men, it has a sub-text of feminine strength, of the nurturing and civilizing powers of women in difficult circumstances.

Though constrained and denied in this narrative of loss and disappointment, the hidden desires of women and children are expressed, as de Certeau reminds us, in disguised and secret ways. The inner lives of my grandmother and my mother and other women of their generations were not destroyed by their circumstances. Their love and strength transformed the lives of those around them, and without them, there would have been no property, no family, no inheritance of pride, strength, intelligence, love and endurance to be passed on to their children.

The spotlight moves to the anonymous supporting cast, and highlights the contribution they have made to the place that women occupy today, as well as the work still to be done.