Belonging is the other side of becoming. When we are becoming, we are always in flux, not fixed, not stationary. When we are belonging, we don’t need to be fixed or get stuck in a particular frame. It was true, in the past, for the majority of people who were not nomadic or displaced, that they lived their lives in one place, in a known community, an enclosed space with rules, mores, codes, rites and punishments. There was connectedness and security, but if you were scapegoated or exiled, if you didn’t conform, in some societies, if you were a woman, a slave or a child, or had a disability, you would suffer judgement, deprivation, even torture or death. Many books have been written about exile, about scapegoating.

Today, we live in flux. Even if we live in one place, the physical world and the technology we use to communicate and do business is changing rapidly. I grew up in the outback, in a small weatherboard house with no power, no phone, no vehicle some of the times, miles from the nearest neighbours. I have seen enormous changes in my lifetime.

I was exiled from my childhood home twice. First, when I was sent away to boarding school at the age of thirteen. Again, when I was fourteen, and my absentee father returned and forced my mother to leave the farm so he could sell it. She mourned that place for the rest of her life. For most of my life, I have not felt at home anywhere; I did for a while when I lived with my husband and children in England. But that dream fell apart, we returned to Australia, and I lost my children. For the rest of my adult life, I was a rolling stone, married again for a while, broke up, got together again (about four times), moved from rented house to rented house, gathering no moss. Finally, in the last eight years, I have settled in a place where I feel at home, I feel more of a sense of belonging than I ever have.

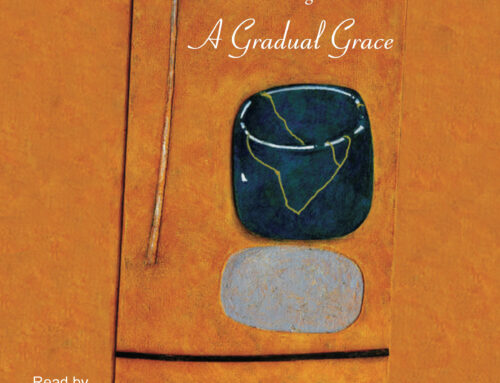

Toko-pa Turner’s 2017 book, Belonging: Remembering Ourselves Home, is about belonging, not to a place, but as a skill that has been lost or forgotten. Turner is a Canadian writer, teacher, and dreamworker who blends the mystical tradition of Sufism with a Jungian approach to dreams.

Home is in the heart and soul. The book is dedicated to ‘the rebels and the misfits, the black sheep and the outsider. For the refugees, the orphans, the scapegoats, and the weirdos. For the uprooted, the abandoned, the shunned and invisible ones.

I put my hand up! She invites us to give up ‘allegiances to self-doubt, meekness, and hesitation,’ to be ‘willing to be unlikeable, and in the process be utterly loved.’ Who could resist this call! In my own life, I have let go of that meek, submissive girl and woman who tried to fit in, to please, to be loved and accepted. I have become strong, my own person, and I have more friends than I ever had when I tried so hard.

This book transcends reviews, since it is so beautifully written, so eloquent and yet so down to earth, that it leaves nothing to say. I have the sense, when I turn the pages, that I am in this world of words, not outside it, and that there is nothing I can add to it. I could extract certain strands; for instance, the author’s life story, which we get glimpses of. It is not the heart of the book, but it is its seed. Toko-pa’s quest for belonging was ‘seeded in alienation. As a nine-year-old, she felt so alienated in her family that she tried to make an abandoned house her own. Her own home was a Sufi ashram, but it was not a safe place for her. Her stepfather was emotionally unavailable and physically violent. Her mother, a yoga teacher and herbalist, was volatile, prone to bouts of depression and rage.

Toko-pa ran away when she was fourteen, and spent the next few years in detention, in and out of orphanages, shelters and group homes, in exile, until she found her true calling. Her initiation was long and painful, as she worked through the wounds of her childhood and suffered guilt for leaving her family, believing it was her own fault she hadn’t been able to fit in. Physically, her woundedness and self-punishment were expressed in a crippling physical illness, finally diagnosed as rheumatoid arthritis. Healing came slowly, through letting herself be loved and looked after by friends and by the man who became her life partner. She emerged from ‘chronic contrition’ and began to work the belief that she could ‘still be lovable even when at odds with others.’

Exile, she teaches, can be a beginning, a turning towards the soul. This lesson is learned through a rite of passage (illness, in her case) and entry into the world of Eros, dreams, and mystery. There are rigorous tests, through which we slowly retrieve our ‘lost or captive parts of the wounded healer’s soul.’

This is such a beautiful lesson, which I have spent my life learning. In entering our woundedness we heal ourselves. We may lose everything, be broken apart, dissolved, dispossessed. We touch the void. Yet, like Jo Simpson in his fall into the crevasse in the Peruvian Andes, by surrendering (literally, in his case, by cutting the rope), we find a way out, we return to life. Of course, we may die in the process. That is a risk we take.

Dreams, in Turner’s dreaming teaching, are ‘the gatekeepers of the underworld.’They can be terrifying, disorienting, confusing. ‘The real bravery of dreamwork is … stepping into our adversaries’ shoes to see how we are also the cruelty that victimises us.

There is so much wisdom and beauty in this book, I could go on and on but I would just be repeating the book. Like a koan, analysis has no place here. The book speaks to our intuitive knowing, our dreaming self, and calls us to a path of belonging from the inside out. I recommend it to fellow travellers.